|

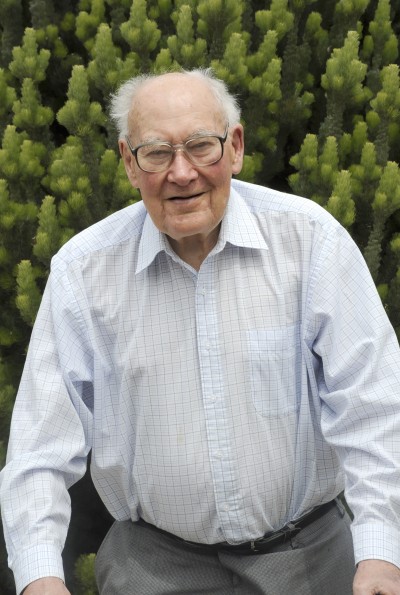

The philosophical community will be saddened to hear that Jack Smart died on Saturday (October 6). He was a figure of huge influence over many years in Australasian philosophy, and indeed in philosophy world-wide. In addition, Professor Smart's constant curiosity about, and interest in all manner of scientific and philosophical matters, and his open, cheerful and friendly disposition, made him much liked by all those who were fortunate enough to know him personally.

There will be a full obituary published in a forthcoming issue of the Australasian Journal of Philosophy.

The Australasian Association of Philosophy expresses its sadness at Professor Smart's death, and offers its condolences to his wife, Elizabeth and his family.

|

![]()

Photo: Steven Morton |

The AAP hopes that this page can be used to collate and share thoughts about Professor JJC Smart. If you leave a post, make sure you add your name at the end, and your email, if you wish.